A flood of input must precede a trickle of output.

This is one of the principles of Teaching with Comprehensible Input. The use of must is one definite in a subject full of ambiguities. I refer to it as the common denominator – that aspect of language acquisition that can level the field for all our students.

The two most important implications of this for me are the following:

1. Nobody achieves fluency without receiving input. Everybody needs a lot. Fluency won’t come without it.

2. Anybody who receives sufficient input will begin to produce language. Anybody.

In first language acquisition, babies get thousands of hours of input before ever beginning to speak. Granted, they’re developing the physical ability to speak at the same time. But they are flooded with thousands of hours of loving, interactive input before they ever say ma ma.

A flood of input must precede a trickle of output.

In early immersion programs like the one my daughter attended, students are not expected to engage in the target language until several months into the second year of the program. She started in Kinder and began interacting with her teacher in Spanish by November of 1st grade. That’s the normal trajectory. That’s roughly 1400 hours of listening to and responding either in English, nonverbally, single word, or short phrases before ever being expected to produce significant interpersonal language with her teacher.

A flood of input must precede a trickle of output.

It’s time that we in more traditional language programs realize that we can create a similar environment. In fact, if we are going to stop alienating 80-90% of our secondary language students and instead reach and teach all or nearly all of them so that they stay in our elective programs, we must begin to discuss ways in which we can deliver high doses of interesting and understandable language to our students without forcing them to produce beyond their level.

How can we allow them to acknowledge their understanding and produce minimally without feeling the stress of having to produce before they’re ready. It’s ironic that almost every world language professional development flyer I get in my mailbox (and I get a lot!) highlights how to “get your kids talking faster” or get them to “get over their fear of talking”. It’s counter-productive.

A flood of input must precede a trickle of output.

In “eclectic” classrooms I’ve taught and observed in, speaking exercises are designed to force speech using particular structures. Directions can be complex. Maybe the teacher needs to give instructions in English to make sure students do it right. Students are obligated to speak unnaturally. While it may be natural to just respond with “Yes” or a short phrase, students are expected to produce the target structure and to produce it accurately. The mind is torn in different directions and spontaneous, subconscious, acquired language is not the result.

In 2007 I began implementing TPRS and in 2010 I began going beyond TPRS into the realm of TCI. My focus has shifted away from spending time thinking up clever activities to make kids use the past preterit. I don’t create projects and require them to add all forms of the verb tener. We don’t spend time contrasting ser v. estar. Instead I’m laser-focused on speaking with them and providing them things to read that they can understand and find interesting. I hardly ask them to speak or write at all. I require them to talk, but only to respond to my questions. Their job is to show me when they understand and show me when they don’t. We call it negotiating meaning.

First they are allowed to answer nonverbally. Soon after they reply with one word. I hardly have to even coach them into stretching their answers into phrases or sentences. Phrases emerge naturally and at different times for different students. And by January, the vast majority are chattering uncontrollably at home, on the way to dance, in the cafeteria and their other classes.

I believe that they want to speak. I believe that’s why they register for class. I don’t believe that making them speak before they’re ready will lead to what we want for anywhere close to the majority of our students. On the other hand, if we put the focus of their job in class squarely on comprehension, if we encourage and applaud any efforts at output, if we avoid over-correction that spotlights what they’ve done wrong instead of celebrating that they’ve produced meaningful language, they will want to speak with each other. At first in their own safe-zones – home, car, with friends or in their own heads – and later in sheltered subject matter classes. A trickle of output will become a flow. And, paraphrasing John DeMado, if they’re the owners of their language, they’ll be more willing and likely to want to renovate or improve their own accuracy over time.

Relying on this common denominator, that comprehension of a language inherently and necessarily precedes production of the language, we can see the opportunity for all our students, not just the college-bound or the high-achieving, to find a path to intermediate levels that will allow them to continue learning and refining their language wherever their lives may take them.

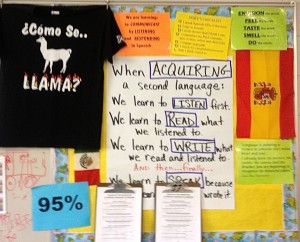

I loved reading this post! Very well said. Thank you for sharing a picture of the poster in your classroom — I believe it is important to remind students how language acquisition works as well. I was thinking about making a similar one for my classroom… What does the last line about “Speaking” say?

Thanks 🙂

Hi Lisa, you are right. Teaching kids not just words but how languages are required is really, really important. Language learning in the public’s eye is so misconstrued. The rest of the poster follows: And … finally… we learn to speak because we listened to it, read it, and wrote it. When I make the next one, I will probably say finally, we speak. That pays tribute to the notion that speech simply emerges when it is ready and it is not something that is learned. Thanks so much for visiting my site, reading and sharing your thoughts!

Really helpful discussion here, Grant. I’ve just pulled a quotation from it for a presentation I will be making at the American Classical League on Friday at the University of Connecticut. With credits to you, of course! Maxiamas gratias!

Bob, as always, thank you for your kind words and for sharing!

I want to hear more about your thoughts on “eclectic” classrooms. I insist to those who attend my workshops that they need to stop doing activities and practicing skills. We should have real simple and authentic conversations with students, discuss books, art, movies, festivals, etc… With your permission I would like to add you post to my collection of resources.

Your thoughts on input and understanding are on the spot, Grant. The students and I discuss the stages children go through in their first languages. While the HS kids are not babies, they still have that early stage where they depend on the teacher for all knowledge, then they experiment. I use TPRStorytelling with legends and historical events for part of my instruction and lots of Comprehensible Input in different settings.

In the past, I encouraged the students to demonstrate their knowledge by drawing, movement, simple yes/no answers, etc – but I didn’t insist that they produce language they weren’t ready for until later in the semester or even year. I noticed that some students were ready to speak quite soon while others allowed themselves time to work towards that goal. There were students who took advantage of that permission, so now I blend a bit more so that everyone has speaking exposure at multiple times throughout the first year. It is all scaffolded and supported for each level, but I do want them to see that language production is possible. The confident students do well and the struggling students receive extra support. As always, the language learning adventure is filled with many stories and experiences. Thank you for sharing your thoughts! Knowing that there are other teachers who focus on commuication and not grammar functions supports our work.

Great article! This is why I created Les sons français. People need to hear the language and be able to identify and sound out words for proper comprehension. In the meantime, they learn to write effectively with learning proper letter combinations.

If you hear it, you can say it. If you can say it, you can read it. If you can read it, you can write it.

I apologize for asking this and please don’t take it critically. How do you grade? I am not asking how you assess. We all know what and how our kids are doing, but there are those accountability aspects, proof we’re accomplishing something, “objective” letters or numbers that result from things like worksheets, tests, oral quizzes, whatever . . . I am asking, when a principal looks at your gradebook to ascertain your records-keeping for any reason, especially in the early months, or a parent looks at the assignments report, what does he or she see? I would love to treat my class like an art class where language use is seen as the art it is, and every unit is like a project with assessments like “improving,” “approaching target,” or something equally fluid and descriptive and ultimately more meaningful than “88%.” Grading programs want numbers and principals want minimum entries per week and quantifiable results. Sigh. Thank you so much for your post. I find it encouraging in its description of your sequence. Oh, I teach 9th-12th grades. One final thought: I find current students’ listening-retention skills quite weak in any language, including in my English (as in English Language Arts, not ELL) class. Thoughts? Thanks for tolerating my mini-rant.

I just found your blog, Grant, and I love your thoughts and ideas. Thanks for sharing! I’m going to start implementing some of your techniques tomorrow. I, like Lorraine, am wondering what your grade book looks like. I always feel like I’m trying to create activities, especially speaking activities to fill the grade book.

Also, in one of your posts you talked about pictures of your classroom. Where can I find those?

Pingback:First We Learn to Listen – Grant Boulanger – Cymraeg Cyfrwng Saesneg